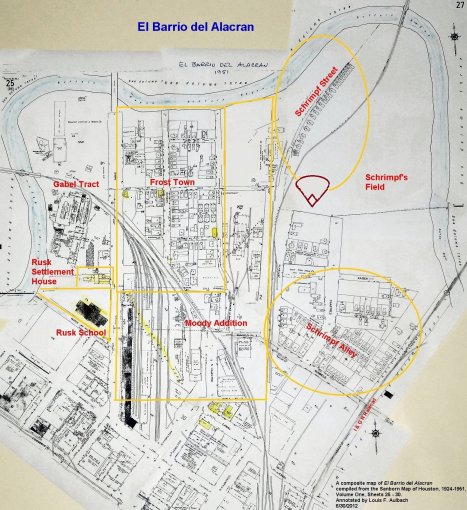

These new residents moved into areas where other Hispanics had already settled and where their Mexican culture was familiar. One of these areas was a part of the Second Ward that had been known generally as Frost Town during the nineteenth century. It encompassed the Frost Town Subdivision, the Moody Addition and Schrimpf's Field. By the early twentieth century, the area consisted of small, run-down homes that were poorly serviced by city utilities. The rents, however, were modest and affordable. During the 1930's and 1940's, this area became known as El Barrio del Alacrán, the neighborhood of the scorpion. It was one of Houston's most notorious slums.

As a community, the Alacrán reflected patterns of other immigrant groups -- gain a foothold in the larger society, adapt and prosper, and assimilate into the mainstream. This process was not always easy. Schools were below par. In the Alacrán, juvenile delinquency was so prevalent that special social programs had to be developed to address the issue. The Rusk Settlement House and, later, the Neighborhood Centers were leaders in this effort.

In the early 1950's, the Alacrán was demolished and replaced by the Clayton Homes public housing project. As well, the Elysian Viaduct and US Highway 59 were constructed through the area. However, the generation that emerged from the Alacrán produced successful members of the community, business men and women, and community leaders. By the 1960's, the Mexican American community was prepared for the challenge of the civil rights movement for Hispanic citizens that would take place in the 1960's and 1970's.

After the founding of Houston by the Allen brothers in 1836, the town grew quickly. Houston experienced a sustained growth in population throughout the nineteenth century, and by 1900, the vast majority of the residents of Houston were of either Anglo-American, European, or African-American heritage. Few Houston residents were of Mexican heritage. The census records from 1850 to 1880 indicate that fewer than twenty individuals with Spanish surnames lived in Houston during that thirty-year period. By 1900, when the population of Houston was 44,6331, only about five hundred people of Mexican origin lived in Houston2.

1 "Houston." Wikipedia. <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Houston> [Accessed June 24, 2012].

2 Roberto R. Trevino. The Church in the Barrio: Mexican-American Ethno-Catholicism in Houston (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2006), p. 25-26.

3 Ibid., p. 26.

4 Jesus Jesse Esparza. "La Colonia Mexicana: a history of Mexican Americans in Houston." Houston History, Volume 9, Number 1 (Fall 2011), p. 2.

5 Louis F. Aulbach. Buffalo Bayou: an echo of Houston's wilderness beginnings (Houston: Louis F. Aulbach Publisher, 2012), p. 385-400, 408-462, 465-476.

6 "School Histories: the stories behind the names." HISD. <https://www.houstonisd.org/HISDConnectDS/v/index.jsp?> [Accessed March 4, 2011].

"Houston, 1907. Volume 1, Sheet 10." Sanborn maps, 1867-1970: Texas.

Betty T. Chapman. "Settlement houses: Havens of help in early Houston." Houston Business Journal, December 29, 2000-January 4, 2001.

7 Ibid.

Betty Martin. "Neighborhood Centers boosting people's lives." Houston Chronicle, Thursday, 08/18/2005. Section: This Week, Z11, Page 1, 2 Star Edition.

"Settlement House Opened." Galveston Daily News, May 5, 1909, page 9.

8 "Summary of news." Galveston Daily News, December 16, 1910, page 1.

Gunter, Jewel Boone Hamilton. Committed, the official 100-year history of the Woman's Club of Houston, 1893-1993 (Houston: D. Armstrong, Inc., c1995).

"New Rusk School opens." Galveston Daily News, April 23, 1913, page 3.

"Houston, 1924. Volume 1, Sheet 29." Sanborn maps, 1867-1970: Texas.

"Mexicans in Houston Today." Houston History. <http://www.houstonhistory.com/> [Accessed January 25, 2005].

Betty T. Chapman. "Settlement house in Second Ward relieved problems of overcrowding." Houston Business Journal, March 14-20, 1997.

9 Sr. Fannie Mae Mead [sic: Wead]. "Frost Town." Genealogical Record, June 1984. Pages 64-67.

10 "Historic Frost Town." Art & Environmental Architecture, Inc. <http://www.frosttownhistoricsite.org/> [Accessed January 10, 2003].

11 Bud Bigelow, photographer. "Schrimpf Alley goes smash." Houston Post, July 6, 1951.

12 Analysis of the 1900 United States Census data for the Frost Town blocks by the author.

13 Analysis of the 1910 United States Census data for the Frost Town blocks by the author.

14 Analysis of the 1920 United States Census data for the Frost Town blocks by the author.

15 Analysis of the 1930 United States Census data for the Frost Town blocks by the author.

16 Gladys Clark. Files, 1986. "Frostown-Moody Ownership Map, 1946." A copy is in the author's possession.

17 William Sebastian Bush. Representing the Juvenile Delinquent: Reform, Social Science, and Teenage Troubles in Postwar Texas. Ph.D. Dissertation. University of Texas at Austin, 2004, p. 90.

Eddie Krell. "They dream of new homes today in Schrimpf Alley." Houston Chronicle, Thursday, January 4, 1951. Page 2.

"Clayton Housing Slated." Houston Chronicle, January 4, 1951. Page 1.

Sigman Byrd. "In the Undecked Halls of Houston's Schrimpf Alley." Houston Press, 12-22-1950, page 15.

18 "Houston, 1924-1951. Volume 1, Sheets 25, 26." Sanborn maps, 1867-1970: Texas.

19 "Houston, 1924-1951. Volume 1, Sheet 26." Sanborn maps, 1867-1970: Texas.

"First Ward." Historic Neighborhoods Council. March 2005. Greater Houston Preservation Alliance.

20 "Houston, 1924-1951. Volume 1, Sheets 25, 26." Sanborn maps, 1867-1970: Texas.

21 "Houston, 1924-1951. Volume 1, Sheet 26." Sanborn maps, 1867-1970: Texas.

"1930 United States Census, Series T626, Roll 2346, Page 122." Heritage Quest Online.

22 Sigman Byrd. "The Street of the Scorpion, Where Death Hath No Sting." Houston Press, Wednesday, February 14, 1951, page 15.

23 Byrd, "In the Undecked Halls of Houston's Schrimpf Alley," 1950.

24 Krell, 1951.

25 1930 United States Census data for Frost Town blocks.

26 "Clayton Housing Slated." Houston Chronicle, January 4, 1951. Page 1.

Sigman Byrd. "In the Undecked Halls of Houston's Schrimpf Alley," 1950.

Krell, 1951.

27 "Our City - City vs Farm." Houston Chronicle, January 6, 1951.

28 Luz Coy Vara. "A hand drawn map of El Barrio del Alacrán by Jesse Coy Vara, 2004." A copy is in the author's possession.

29 Sigman Byrd. "The Street of the Scorpion, Where Death Hath No Sting," 1951.

30 F. Arturo Rosales. "Mexicans in Houston: The struggle to survive, 1908-1975." Houston Review. Volume 3, No. 2 (Summer 1981), (Houston: Houston Library Board, 1981), p. 224-248.

31 Roberto R. Trevino. The Church in the Barrio: Mexican-American Ethno-Catholicism in Houston (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2006), p. 30.

32 Luz Coy Vara. Personal communication. October 10, 2004.

33 Félix Fraga, 1929-. Houston Oral History Project, September 14, 2007. Houston Public Library. (http://digital.houstonlibrary.org/oral-history/felix-fraga.php , Accessed June 18, 2012). Felix Fraga, a former City Council Member and a Vice President of the Neighborhood Centers, is probably the most notable person to have come out of the Alacrán. Although the Fraga family lived on McAlpine Street, about four blocks from the Alacrán, Fraga attended the programs of the Rusk Settlement House as a child and played youth baseball at the ball field in Schrimpf's Field.

34 Ibid.

Arnoldo De Leon. Ethnicity in the Sunbelt: Mexican Americans in Houston (College Station: Texas A & M University Press, 2001), p. 27-28.

35 Vara, Personal communication, 2004.

36 De Leon, p. 27.

Fraga, 2007.

37 Ibid.

De Leon, p.56.

38 De Leon, p.105, 108.

39 Manuel Pena. The Texas-Mexican Conjunto: History of a working-class music (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1985), p. 140, 143.

40 Ibid.

Thomas A. Krenek. Mexican American Odyssey: Felix Tijerina, Entrepreneur and Civic Leader (College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 2001), p. 64-65.

Jesus Jesse Esparza. "La Colonia Mexicana: a history of Mexican Americans in Houston." Houston History, Volume 9, Number 1 (Fall 2011), page 4.

41 De Leon, p. 105-106.

42 Bush, 2004, p. 90.

William S. Bush. Who gets a childhood?: Race and juvenile justice in twentieth-century Texas (Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 2010), p. 47-48.

43 Thomas McWhorter. "Trailblazers in Houston's East End: The Impact of Ripley House and the Settlement Association on Houston's Hispanic Population." Houston History, Volume 9, Number 1 (Fall 2011), p. 11-12.

44 Bush, 2010, p. 53.

45 Ibid., p. 48.

46 De Leon, p. 109.

47 Vara, "A hand drawn map of El Barrio del Alacrán by Jesse Coy Vara, 2004."

Fraga, 2007.

Frank Fraga, personal communication, May 22, 2010.

48 Esparza, p. 4-5.

Fraga, 2007.

49 Sigman Byrd. "'The Houston Story': Notes on a bookman and his book." Houston Press, 04/12/1951.

50 "Houston, 1924-1951. Volume 1, Sheet 28." Sanborn maps, 1867-1970: Texas.

Kirk Farris. Personal communication. August 17, 2003.

51 "Schrimpf Alley slums fade." Houston Chronicle, August 5, 1951.

52 "Mrs. Clayton aids in cleaning up of Houston slum area." Big Spring Daily Herald, January 4, 1951, page 3.

53 "Clearance week for new 348-unit housing project begins today." Houston Post, July 5, 1951.

Larry Evans, photographer. "First Schrimpf Alley Family." Houston Chronicle, July 4, 1951.

Bigelow, 1951.

54 De Leon, p. 101.

55 "Who we are." Preservation Texas. <http://www.preservationtexas.org/about/index.htm> [Accessed August 29, 2005].

56 "Public Housing Debate: Houston's public housing fight of the 1940's - 50's." Texas Housing. Texas Low Income Housing Information Service. <http://www.texashousing.org/txlihis/phdebate/past 113.htm> [Accessed August 7, 2001].

Mike Snyder. "Public housing, private hopes / City planners look to project as a catalyst." Houston Chronicle, Sunday, 10/25/1998. Section: A, Page 33, 2 Star Edition.

"US 59 proposed route across Buffalo Bayou, 1955." Texas Freeways. <http://www.texasfreeway.com/Houston/historic/road_maps/images/> [Accessed August 29, 2005].

57 "Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics: 2010 Demographic Profile Data. Houston, TX." American Fact Finder. U. S. Census Bureau. <factfinder2.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?src=bkmk> [Accessed August 5, 2012].

Copyright by Louis F. Aulbach, 2012